(The Eastern Maine Canoe Trail was an historic route rediscovered by Mike Krepner, whose vision helped inspire the Northern Forest Canoe Trail. Mike passed away in November 2018. This story was originally published in 1997 by the Portland Press Herald newspaper in eastern Maine. It was reprinted with permission.)

ON THE ST. CROIX RIVER – Sheets of rain are streaking across the St. Croix River in eastern Maine, on the Canadian border. It’s the second morning of our three-week canoe trip, and the journey is already testing us.

Despite rain gear, we’re drenched by the time we paddle to Loon Bay, four miles and a couple of hours away from where we had camped. Wet, shivering and hungry, our clothes sticking to our skin, we trudge uphill on the Canadian side to a lodge that holds the promise of a roof and maybe a warm drink.

No such luck. The lodge is closed, but the owner lets us dry out under a log-sided picnic shelter. We eat. The rain eases. We feel better. We get back in our canoes.

But the dark sky brings more rain, and the downpour resumes. We bail the canoes to keep them from filling with water. Everything is soaking wet. Wet and cold. Rumbles of thunder and an occasional lightning streak add to our discomfort.

This can only get better.

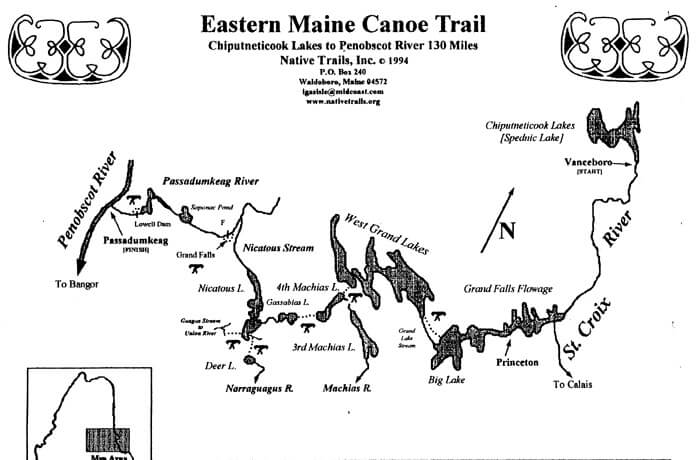

For three weeks, these waters will carry us 130 miles down the St. Croix River and over the lakes and streams of eastern Maine. My companions are John Patriquin, a photographer for The Portland Newspapers, and Amy Sinclair and Don Couillard, a reporter and a cameraman for WGME-TV. We’ll traverse forest portages. We’ll move through watersheds. And if we close our eyes and imagine, we will span time.

For these are the same waters that have been highways for Indians, footholds for settlers and sluiceways for logs.

For more than a thousand years, the watery web of lakes and rivers etched across Maine’s forested landscape was the equivalent of today’s highway system. With the advent of birch-bark canoes, native people were able to move about the state along these travel routes.

In the 20th century, paved highways and logging roads eliminated the need for these historic water trails. But many still exist, largely unchanged. Now, these trails are being rediscovered. One route – the one we are traveling – connects the St. Croix River on the New Brunswick border with the Penobscot River north of Bangor. This 130-mile route has been dubbed the Eastern Maine Canoe Trail.

Organizers see the trail as a prototype for a more ambitious idea – a 700-mile water route stretching from New York state to northern Maine. They envision the day when canoeists will be able to follow a series of ancient Indian waterways and portages from Fort Kent to Old Forge, N.Y. It would be called the Northern Forest Canoe Trail.

Organizers see the trail as a prototype for a more ambitious idea – a 700-mile water route stretching from New York state to northern Maine. They envision the day when canoeists will be able to follow a series of ancient Indian waterways and portages from Fort Kent to Old Forge, N.Y. It would be called the Northern Forest Canoe Trail.

There are challenges. In northern Maine, for instance, timberland owners are leery of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail proposal. They fear private property rights would in time lose out to the public’s desire for a wilderness-like experience.

Still, efforts to establish water trails are under way on rivers including the Penobscot, Androscoggin and Kennebec. People are learning the history of ancient water routes and trying to gain and preserve access to them for modern recreation travel.

Journey begins in Vanceboro

Our trip starts off pleasantly enough.

We begin in Vanceboro – where Larry Doyle can turn the St. Croix River on and off. Doyle, a dam attendant for Georgia Pacific Corp., controls the flow of water at seven dams in the St. Croix watershed. His job is to provide enough water for hydroelectric power while keeping appropriate levels in the lakes behind the dams.

On this day, he has 700 cubic feet per second of water coursing through the garage-door-sized gate – enough water, he tells us, to float our boats. I ask Doyle, only half in jest, if he can give us another 100 cubic feet, to give us a nice boost.

He smiles. No way. He’s waiting for us to move on, so he can cut the flow by two-thirds, because highway workers are set to tear out an old bridge pier that has been replaced downstream, at the Vanceboro border crossing into St. Croix, New Brunswick.

Below the dam, the St. Croix is narrow and fast. Roads are close by, but the river is lined with cedars and largely undeveloped. It retains a wild feel.

The St. Croix is an exciting river. A dozen rapids in the first 20 miles keep canoe paddlers paying attention. That’s especially true 10 miles below Vanceboro, at Little Falls. We hear the roar of the water and take out on the right bank.

That’s where we meet Tony Reader, a volunteer for the St. Croix International Waterway Commission. With the blessing of Maine and New Brunswick, the 10-year-old group is carrying out a management plan for the river to determine what the water flow should be to generate power, where campsites should be located and how the river should be used for recreation.

Reader is traveling by canoe this day, inspecting campsites for fire safety. ”Little Falls is a disaster area,” Reader says, surveying the campsite, which has been trashed by teen-agers partying there. ”We have a lot of work to do here.”

Fortunately, he’s getting help from a group of teen-agers who are rebuilding the fire pits.

Little Falls is a party place, accessible by car. Overuse is a problem. Kids come here, from both countries, to sit on the rocky bluffs and watch canoeists negotiate the moderate (Class III) rapids.

After carrying our gear out of the canoe and around the falls, we take a wild ride through the white water. The ride lasts only 30 seconds or so, and it goes by in a blur. We’re not so much enjoying it as trying to keep the bow facing downstream so we don’t crash.

We get through the white water fine, put our gear back in the canoe and continue downriver.

The St. Croix is so clear today that it’s hard to imagine it choked with logs. But below the surface, piles of sunken pulpwood tell the tale: Every winter for about 100 years, until the early 1970s, loggers piled logs on the ice-covered river, and in the spring the logs floated to mills downstream. Some of them sank along the way.

We steer the boats into an eddy and hike upstream. At the end of a narrow path is a clearing and a gravesite surrounded by a black railing. Inside are a small cross and grave marker. It reads: ”Child found in the river burried here June 29, 1899.” This site, we have been told, has been maintained by loggers. No one knows anything else about it.

Back in the canoe, we’re anxious to find a campsite at the end of our first day on the water. We’ve been paddling for 15 miles – all day – and we’re getting hungry and want to call it a day.

We make camp near Albee Rips, on the Canadian side. It’s a sunny, warm evening, so we bathe in the river and wash our clothes and relax.

Day two brings downpour.

The next morning, we wake to the gentle patter of rain on the tent fly. We could use a shower, I say to myself. It’s been a dry summer.

Not any more. Instead of a shower, we get that miserable, daylong downpour – and then some.

As daylight fades on day two of our trip, we reach a campsite at Kendrick Rips, near the Grand Falls Flowage. Beneath a dripping tarp, we fix supper and hope the torrent will let up. It does not.

By now, it is almost dark and the mosquitoes are swarming. Out come our tents, still soaked from the downpour when we broke camp in the morning. Assaulted by rain and bugs, I carefully place my foam mat and sleeping bag on the wet tent floor. Within minutes, both are wet. Soon, I’m in darkness, my body enveloped by water, curled in a fetal position.

It rains all night. At dawn, it’s still pouring, so no one moves. Besides the relentless rain, there are still too many bugs around for us to dare step out of the tent.

By mid-morning, the sky brightens. We gather up our soggy gear and head downstream. With glimpses of blue and a clearing wind pouring out of the west, we cross Grand Falls Flowage and pull up on the beach in Princeton.

By now, the sun is shining and we empty all our gear onto the town beach. The tents go up, sleeping bags are spread out, fences become clothes lines and every piece of soggy dunnage is open to the air. Local kids come by and gawk. The place appears as if L.L. Bean has set up an outdoor showroom. Within hours, everything is dry.

We head across Lewey and Long lakes and through the narrows at Peter Dana Point, a focal point of the Passamaquoddy community at Indian Township. Past the narrows, on the shores of Big Lake, we see Wayne Newell’s 17-foot runabout tied up at his dock.

Newell is a tribal councilor, educator and preserver of Passamaquoddy culture. When we double back to visit him the next day, he sits with us by the lake and talks about the historic importance of waterways to his people.

In his own life, Newell says, he feels the connection. Sometimes, he will take his boat out into Big Lake and drop anchor. Largely undeveloped and tranquil, the lake appears as it did centuries ago. So he will sit at anchor and try to imagine small fires along the shore and his people catching bass to smoke over the flames.

”There was a tranquility I can only imagine,” Newell says of this scene. ”It’s a way for me to get closer to my ancestors and what they did.”

But Newell’s stories would wait for us, because on this glorious, wind-swept afternoon, with the sun setting behind fair-weather clouds, we are pressed for time to make camp. Newell had told me about a beach past the township, on Governor’s Point, a heavily wooded area with big red pines and a panoramic view of the lake. We have it all to ourselves.

That night, as a quarter moon glides west past a million stars, we slide into our sleeping bags, warm and dry. With the prehistoric laugh of loons echoing across the water, we fall asleep.

GASSABIAS PORTAGE – I don’t know which is worse – my arms and shoulders aching under the weight of the 80-pound canoe over my head, my constant tripping over tree roots and slipping off logs into calf-deep muck, the mosquitoes and deer flies biting me, or the 80-degree heat and searing sun that has left me dehydrated and bathed in sweat.

Maybe it’s just that all these things are happening to me at once.

Mike Krepner can talk all he wants about Indians and history and heritage, but this is two miles of hell.

It was Krepner and his friends who in 1985 reopened this centuries-old canoe carrying route between Fourth Machias Lake and Gassabias Lake. The Gassabias Portage is the only carry along the 130-mile Eastern Maine Canoe Trail that’s inaccessible by road. And in the view of Krepner, who takes some perverse delight in carrying a canoe over his head for miles, this is the most difficult portage in Maine.

Over the next four hours, we would learn why.

The Gassabias Portage is a bruising climax to a week that had gone well.

Our canoeing team, with newspaper photographer John Patriquin in my boat and WGME-TV’s Amy Sinclair and Don Couillard in the other, leaves after sunrise Tuesday, July 15, from the fishing village of Grand Lake Stream to travel up West Grand Lake.

With a gentle breeze at our stern, we make good time on our journey across Maine’s eighth-largest lake. As we leave the cove at Grand Lake Stream, the view opens up. The rolling forest looms ahead like folded strips of green velvet, sewn between blue sheets of water and sky.

Soon, we arrive at the Thoroughfare, a narrow waterway between West Grand and Pocumcus lakes. Here, we meet Jack Perkins, a Maine Guide and builder of the renowned Grand Laker canoes. Perkins is caretaker for a rustic family compound at the Thoroughfare, and on this day he is doing chores to prepare for the family’s August visit.

But he makes time to take us on an arrowhead hunt.

The Thoroughfare is a natural passage between two lake systems. For thousands of years, Indians camped here on the sandy beaches and speared fish passing through the narrows. They left behind many artifacts, including two flint arrowheads Perkins found recently. But after hours of combing the shoreline, all we have is an appreciation for how many pointy pebbles look like Indian artifacts.

The next day, we continue on to The Pines, a 130-year old sporting camp on lower Sysladobsis Lake. There, we rendezvous with Mike Krepner, his wife, Ellen Libby, and their two malamute huskies, Vuka and Tuktu. They’ll be joining us for the Gassabias Portage.

Meanwhile, WGME switches its television crew, and we’re joined by reporter Marnie MacLean and photographer Jack Amrock. It’s time for Couillard and Sinclair to say goodbye, or, as Sinclair puts it, ”head back to the land of flush toilets.”

Smart move.

Ravens circling our camp Thursday wake us before sunup with their persistent cries. It is just as well. A long day awaits.

We put our three boats in at the top of Fourth Machias Lake and paddle into a glorious morning. Fourth Machias may be my favorite water body on the trail. Islands, marshes and distant mountains create a diversity of views. The glaciers left behind a pronounced esker, a sand and gravel ridge, along the west shore that is dotted now with stands of red pine and white birch. At spots, the esker spills down to the lake to form beautiful sand beaches.

By 9 a.m., we complete our four-mile paddle down the lake and slip into a winding creek. We follow a twisting channel, lined with purple, flowering pickerel weed. Finally, we spot a brown sign stuck in the muddy shoreline. It says ”portage” and depicts a person with a canoe overhead. This state-owned area is part of the 25,000-acre Duck Lake public lands unit. Conservation workers put up the sign last year.

Krepner is excited to see the sign. He hasn’t been here in 12 years. The sign represents an official recognition of this place, which was a key link to the historic travel routes of eastern Maine. To one side lay the Penobscot River drainages; to the other, the St. Croix and the sea.

I think, what’s two miles when you’re going 130? So we swap our water shoes for hiking boots and drag our boats onto the shore.

First off, I can see this isn’t really a trail, which is a beaten path. We’re standing calf-deep in a cedar swamp. Where the water’s deep, Krepner and others have laid crude log bridges. These slippery, unsteady spans give the appearance of a trail. And they’d be OK if you were carrying a day pack. But as Patriquin helps me steady our 80-pound canoe over my head, I instantly recognize why wilderness canoe portages have fallen out of favor as a mode of travel.

Within minutes, my arms feel like rubber. I stumble over the logs and trip on rocks as I attempt to negotiate this so-called trail. When I can no longer stand, I toss the canoe aside and collapse.

Next, Patriquin takes a turn. I gather up the paddles, day packs, photo equipment and life vests and follow. Behind me, Marnie MacLean is hefting a boat. But soon she loses her footing and falls.

And where’s Mike Krepner? Up ahead, toting his boat like he’s taking a walk in the park.

We eventually catch up to him as we enter the start of an old-growth forest preserve. Here, 200-year-old red and white pines tower over the landscape. I’d appreciate them more if I wasn’t exhausted, covered with bug bites and cuts, and sweating like a pig.

Krepner says we’ve gone almost a mile. It took two hours.

We sit on the mossy forest floor and have lunch. I daydream about reaching Gassabias Lake, ripping off my shoes and diving into the cool water. Speaking of water, we’re not drinking enough. We fill our canteens in a puddle.

I size up our crew. They’re holding up. But what could we do now anyway? We’re halfway through hell, and there’s no turning back.

The old growth is high ground, and the trail here is real and level. Krepnersays we’re entering the home stretch. Patriquin puts on his life vest and, aided by the extra shoulder padding, makes a few heroic canoe carries through the forest. We’re cruising now.

But as we leave the old growth, the trail narrows. Now we’re in a peat bog. Patriquin and I are carrying our canoe together, end to end, sloshing through a narrow trough of muck. Finally, we decide to untie the canoe’s bowline and drag it through the bog like a sled.

At a rest stop, Patriquin walks ahead to scout the route. He comes back at 1:30 p.m. and says he has seen the lake. Soon, I can see water through the windblown trees.

It’s anticlimactic. We’re all too numb to enjoy this moment.

We reach Krepner, Libby and the dogs, sprawled out near the shore. At least he looks tired. But he says it was a great experience that he had been looking forward to, just to see the route again. And aside from the signs and some modest trail work, not much has changed.

And he puts a positive spin on the situation.

”Heading to the Penobscot River,” he says, ”it’s all downhill from here.”

I say: You’re an evil man, Mike Krepner, to make people do this.

But there’s no time to joke around. And forget about that cooling swim. Gassabias Lake has 2-foot swells and whitecaps. The wind is gusting, and the sky is threatening. We still have a two-mile paddle across this mess to our car.

As we push off into the wind, I look back with some satisfaction. We have safely completed the Gassabias Portage. And I know I will never do this again.

NICATOUS DAM

Flames dance in the barbecue pit as workers at Nicatous Lodge toss on logs to boil water for a Friday evening lobster bake. On the night of our visit, 30 guests are sitting at picnic tables on the waterfront lawn, and the rising moon casts a yellow glow across Nicatous Lake.

Such a scene would have been hard to imagine 40 years ago.

Back then, thousands of four-foot logs choked the cove and obscured the water surface. Anyone sitting around probably was waiting for the lake to rise so that rafts of wood could be driven through the dam for a 40-mile ride down the Passadumkeag River and its tributaries.

Timber harvesting survives in this region. But the contrast between boom times past and the pace of life now is striking to our canoe team as we conclude our journey across Nicatous Lake and the Passadumkeag River.

Here, we see the restorative powers of nature as we move through an all-but-forgotten corner of Maine, brimming now with wildlife. Away from the lodge, we come upon more moose and deer than people.

We also notice the character of the landscape is changing. After almost two weeks in a boreal forest of spruce, pine and cedar, we start to see the maples and oaks more typical of southern Maine.

The changing landscape makes me think about all we have seen and the people we have met since leaving Vanceboro and the St. Croix River more than two weeks ago.

I appreciate that the Eastern Maine Canoe Trail isn’t a static experience, with log drives then and lobster bakes now. It’s a living history. Events and time blend and flow here. The old ways of native people and settlers intermingle with the present. And in subtle ways, they suggest a future.

The changing scenery really hits home for us on Gassabias Stream, a four-mile flow connecting Gassabias and Nicatous lakes.

This twisty stream looks like a southern swamp, dotted with dead trees and populated by ducks and ospreys. And as we round a bend, I’m surprised, on this placid stream, to hear the rush of water.

Beaver dams. Impoundments that the Army Corps of Engineers would envy. A half dozen times, we’re forced to drag the canoes over 3-foot-high walls of sticks and logs holding back the stream.

And while we see no beaver here, we startle two otters playing on a log. More curious than afraid, they watch my approaching canoe before diving below water. And in a parting gesture, one follows the boat, surfaces and lets out a bark.

It’s late in the day by the time we traverse Nicatous Lake and reach the lodge, at the outlet to Nicatous Stream. The lobster bake is being set up. Later, I would learn how the scene clashes with the memories of Charles White and Roger Tourtillotte, two local men who worked near this place in the 1950s.

White is 82 years old. Tourtillotte is 76. When they were young, they would come here in the winter to cut timber off the lake shores. The wood would be dragged onto the ice with horses and contained in a boom. With the spring thaw, workers would hold back water at the dam until the lake rose. Then they would lift the dam gates and sluice thousands of logs down Nicatous Stream to the Passadumkeag River.

”Anything that went out of the stream,” Tourtillotte recalls, ”we had to go pick it out with poles.”

It was hard work, and neither man enjoyed it. But they each worked the drives for five years.

Tourtillotte says he did it ”to keep from starving. Pulp wood was the only thing to do here.”

The men helped guide the wood 40 miles to the town of Passadumkeag, where the river meets the Penobscot. On our journey, they met us at a breached dam that had powered a mill in their once-prosperous town. As they spoke, a great blue heron landed near the foundations of what was once known as Leonard’s sawmill. Hundreds of men found work here around 1900, at the mills and log booms.

Today, memories are housed in a former church owned by the local historical society. On the walls hang weathered scaling tools, giant rulers that helped measure the volume of wood, and black hobnail boots, which gave men footing on wet, slippery logs.

But that era is hard to detect as we head off the next day on Nicatous Stream. We see an occasional sunken log on the stream bed. But we are also impressed with the beauty of the gravelly river bottom, filled with darting minnows. In places, the bottom is clad with a light green grass that waves in the current like long, flowing strands of hair.

And when we do finally reach the Passadumkeag River, below the roar of Grand Falls, we enter a stretch that might as well be a nature preserve. Although a paved road is close by, we see more wildlife in the final 30 miles of our journey than we did on the first 100.

A big treat comes when we see a young bull moose resting on a muddy shore. The photographers have been waiting all trip for this sort of photo opportunity. And the moose patiently poses for 10 minutes, munching ferns and tree branches to kill the time.

Moose and deer have left their tracks on a sand beach at Saponac Pond, where we make camp in the shadow of 1,463-foot Passadumkeag Mountain. A group of local residents wants to develop a small ski area on the mountain’s opposite side. It would take water out of the river to make snow. But plans are moving slowly. Supporters are trying to win a federal grant for a feasibility study.

I think about the log drives and how little evidence remains of their impact on the landscape. Will chairlifts some day mark man’s attempt to wring a living out of the natural resources here?

We decide to make a final push for the Penobscot the next day and wake at dawn. The air temperature is a chilly 45 degrees. The lake is shrouded in swirling mist. Bullfrogs, loons and woodpeckers provide background music as we gear up for a 21-mile day.

We paddle first through an eerie deadwater of flooded pines and maples, created by a small hydroelectric dam in the town of Lowell. Our passage disturbs a beaver, who slips off a rock and flaps his tail at us. We begin to see camps and homes along the shoreline but are gratified, at Rocky Rips, to surprise a buck deer and doe out for a morning drink.

Past the rips, the tree-lined riverbanks fade away and the horizon opens into a stark expanse of marsh and meadowland. Here, the Maine chapter of the Nature Conservancy has been given hundreds of acres along Cold Stream and Ayers Brook, habitat of a rare mayfly.

Looming ahead is the 60-foot-high Enfield Horseback. This sand-and-gravel ridge, or esker, was left behind 14,000 years ago by the glacier. The river cuts through the esker on its way to the town of Passadumkeag. It’s a sign that the Penobscot River is only a few miles away.

This long day has given me a chance to think about how parts of the state’s heritage unfold along the Eastern Maine Canoe Trail and how the past blends into the present.

We have passed dams that once held back water to move logs and now define the character of the waterways for recreation and hydroelectricity. We have learned how the long presence of Maine’s Indian tribes can be captured in an arrowhead or witnessed in a rock carving. We have seen how the hunting and fishing traditions at century-old lodges are expanding to attract new guests to their rustic charm.

Above all, I’m left with the sense that the features that make the Eastern Maine Canoe Trail special will endure. This isn’t the Allagash or the Penobscot’s West Branch, with fabled white water. There are few attractions here to lure big-city adventure seekers. The appeal here is subtle, rugged and genuine. Hopefully, it is timeless.

I think about these things as we come upon the breached dam in the town of Passadumkeag. We are smiling and excited as we pass under the Route 2 bridge and enter the vast, flooded plain of the Penobscot. We have reached our goal.

For a brief moment, I consider that we could turn left here and float down to Bangor. Soon, we’d be in Penobscot Bay and the sea. That’s what people did for a thousand years, in their birch-bark canoes over Maine’s watery highways.

For a brief moment, I take comfort just in knowing that this route, used by people of prehistory, remains open for boaters on the cusp of the 21st century.

Support the Northern Forest Canoe Trail by donating to the Mission Fund.