In mid-August of 2003, my friend Cynthia, a Mainer and artist, phoned and said: “I thought we were going canoe-camping this summer.”

“I don’t know. It’s getting close to the start of school,” I said.

“I found all these great lakes and ponds in the Quiet Water Canoe Guide Maine,” she responded. “Let me read you the descriptions of four or five.”

“I’m not sure we want to go — Mars is going to be really close to the earth this month. Closer than it’s been in 60,000 years,” I said, thinking that we had never canoe-camped together and I had been only once.

“We could see Mars over the water in the Maine North Woods with no nearby city lights,” Cynthia continued.

“Astrologers from the far East predict Mars’ closeness will bring natural disasters, trouble between people, and plain old bad luck.”

“Joanne, don’t be ridiculous. I saw the news about Mars too. NASA says that Mars will still be 34.65 million miles away. That’s way too far to have any effect on us.”

“I guess so,” I reluctantly agreed.

We had a long discussion about the possible lakes Cynthia had found. Our final decision was Lobster Lake, described as remote with few other campers in the quiet water guidebook; it’s north and a little east of Moosehead Lake in a wilderness conservation area. Its name comes from its lobster-like shape, with two sections: Big Claw and Little Claw. We chose to camp in Little Claw, the more tranquil section.

Just in case we couldn’t find dry firewood, we brought a camp stove along. I also borrowed a three-person tent. I had seen the tent set up and had verbal instructions on how to do it. We felt we were well prepared.

Starting at Cynthia’s house, we drove north to the Golden Road, paid our fees at Caribou Checkpoint and continued to the put-in. After loading our canoe, we paddled down Lobster Stream into Lobster Lake, hugging the southern shore to be sure we got into Little Claw. All the campsites were full except the last one, which we claimed. We hauled our gear up the steep slope to our tent site. Mars came closer to Earth.

Back in the city, on my friend’s lawn, the tent looked great with plenty of room for sleeping bags and gear. All I had to do was remember the set-up instructions. As our campsite darkened, after an hour or so of inserting pole A into loop B then inserting pole C into loop E — or was it pole A to loop C then pole B to loop E? — the tent was finally upright and stable.

That night, we discovered that the superior tent had a disabled zipper; it only zipped up on one side, Cynthia’s. Every night a wind blew through my side in our protected campsite in the calmest section of the lake. We tried to fix the opening with bungee cords, rope or twine with no luck.

The next day, we decided to look for moose around one side of Big Island in the middle of Little Claw. There was a photo of a mother moose and calf in the guide book. Surely we would find some. We easily paddled across, but saw no moose. Returning, if the two of us paddled as hard as we could, at exactly the same time, we made headway against the wind on the tranquil section of this quiet lake in Maine.

When we got back to camp, I wrote this poem:

Paddling. Paddling.

Paddling. Paddling.

Hard against the wind

Dark rolling waves

Wind in the deep pine forest

Water washed rocks waited for us

Storm clouds overhead

White caps

Paddling. Paddling.

“Stay close to the shore!”

“Don’t go so far out!”

At last around a bend

A cove and beach

A bleached white log

Shelter, sun, sandwiches

Friendship.

The following day was cloudy and then drizzly — nonetheless, we walked along the shore to the trail up Lobster Mountain. Surprisingly, the mountain was not shaped like a lobster. It was not shaped like any mountain we knew either. It had no real peak. At least there was a good view of the lake from its high, long, flat area.

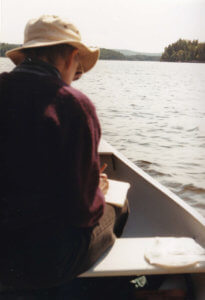

When we got down, the drizzle had abated. I fished from the shore while Cynthia sketched. No fish. I was sure Mars had affected them. Cynthia reminded me that just because I had a fishing license, didn’t mean I would catch fish.

Every night we waited for the clouds to clear so that we could see Mars. Finally, on the night of Aug. 27, 2003, the drizzle stopped and the clouds dissipated. There above the darkened trees, far from the lights of any city, across the lake, was Mars — the size of Venus, as bright as the moon. Its redness reflected in the water. The sight of Mars over the wild Maine woods was awesome and otherworldly, even though it was 34.65 million miles away.

Cynthia cooked lots of wonderful food over a wood fire: steak, potatoes, corn and green beans from my garden. It seemed to me that we had used the stove sparingly. The night after we saw Mars, a wind blew up as we were lighting the stove. Cynthia thought the wind blew out the flame. We put the stove in a more protected spot. We tried again and again to light it, with no luck. No more fuel. We had a cold dinner: ham sandwiches and water.

The next day was our last and we packed up to leave. Now the wind direction was reversed. We doggedly paddled into it hugging the shore. As we came around a point, a great blast of wind pushed us back. Paddling as hard as we could, we could not get around it. We had to paddle in to shore.

“We’ll have to stay here tonight,” Cynthia announced.

“I have to go to work Monday,” I responded. “We can’t spend the night.”

We waited maybe 30 minutes and tried again. Paddling, paddling, paddling, paddling. Suddenly we were around the point. The water was calm! There on the shore we saw a black bear cub pawing at wild cherries in a tree it had bent over.

“Fabulous,” we said. As we rummaged for our cameras, the bear cub took off. We have only a memory.

On the way back to Lobster Stream, we spoke to a man in a motor boat. He told us that he always uses a motor boat on Lobster Lake. His canoe had once been blown to the south end of the lake. He had to walk along the shore pulling his canoe to get back to his camp.

We returned safely in spite of the effects of Mars’ closeness to Earth: extended tent set up time, a disabled tent zipper, running out of stove fuel and wind much stronger than we could paddle against. Mars spun along in its orbit away from Earth.